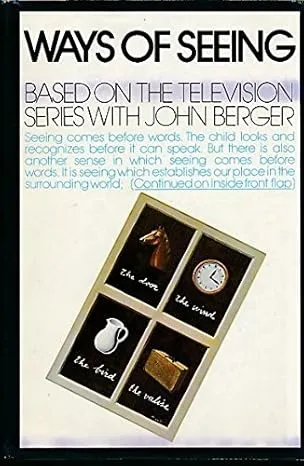

About this book

Five Key Takeaways

- Seeing shapes our understanding of reality and identity.

- Our perceptions are influenced by cultural and personal context.

- Women are often objectified in traditional art representations.

- Art's meaning transforms depending on its contextual framework.

- Publicity images mold our desires and reflect consumer culture.

-

Seeing Shapes Our Understanding of Reality

Long before we articulate with words, seeing helps us understand our surroundings and ourselves. This visual perception provides our first connection to the world.

Seeing isn’t just looking. It’s a dynamic, active process influenced by culture, emotions, and personal experience. This turns sight into a blend of intellect and feeling.

For example, while fire represented Hell in the Middle Ages, today’s views differ drastically. The meaning of what we see adjusts with cultural shifts and knowledge.

Our visual processing also involves the relationship between viewer and object, highlighting that we don't look at things in isolation but integrate ourselves into the scene.

This interconnectedness means every act of seeing impacts interpretation. Even our awareness of being observed influences how we behave and self-perceive.

Visual creations like photos and paintings amplify this impact, as they capture the creator’s subjective "way of seeing," presenting additional layers of interpretation to viewers.

The meanings and histories behind what we see directly impact today’s societal behaviors and mindsets. This demonstrates that vision isn’t neutral—it’s deeply contextual.

Ultimately, seeing is not passive. It is tightly woven into history and human understanding, influencing how we survive, build relationships, and interpret the world (Chapter 1).

-

Context Transforms the Meaning of Art

The problem is: We often miss how environment and context change the meaning of art and images. This disconnect reduces our understanding of deeper meanings.

Art and images never exist in isolation. Their interpretation is linked to their location, history, and cultural narratives. Neglect of this fact distorts their intended messages.

When art is placed in museums, its meaning “elevates.” In advertising, however, art is stripped of original intention and converted into a commercialized symbol.

The significance in any given piece is fluid—it mutates depending on its surroundings, purpose, and how it’s displayed. This makes context pivotal to interpretation.

Berger argues that understanding cultural narratives and selecting art meaningfully can unlock their depth. Without this awareness, our connection with art remains shallow.

He further asserts curators’ selection processes amplify how some art gets prioritized and others are forgotten, influencing which societal stories prevail.

Recognizing these shifts allows us to critically assess which cultural perspectives dominate and challenge ideas purely derived from "how something looks."

By valuing context, we deepen our emotional and intellectual experiences of art. Berger’s perspective invites us to explore more than surface visuals (Chapters 4-6).

-

Women Are Viewed, Not Equal Participants

The problem lies in how traditional European art positions women not as active characters, but as entities shaped and judged through the "male gaze."

This dynamic reduces women to appearances, causing identity splits: how they see themselves and how they believe men view them. This restricts authentic individuality.

For centuries, women adjusted their actions, identities, and even self-worth based on male evaluations. They learned to "survey" themselves out of regular habit.

Berger highlights the imbalance—the judgement of women through men’s eyes perpetuates outdated norms, reinforcing objectification in art and modern media alike.

The tradition of nude painting epitomizes this imbalance. Instead of empowering nudity, it reduces women to objects of pleasure or scrutiny, denying autonomy.

While women's representation is evolving, these roots have left an enduring impact on media and advertising today, where perceptions remain shaped by this lens.

This skewed portrayal limits not just women's roles in society but their ability to develop personal self-worth independent of societal norms.

Berger calls on viewers to identify this bias in art and realign their perspectives to understand women as participants in—not just subjects of—the narrative (Chapter 2).

-

Images Are Not Neutral Influencers

Images shape perception by subtly influencing how we think about ourselves and the world. Their power comes from their ability to embed strong yet indirect suggestions.

Modern societies are inundated with imagery, from advertisements to social media posts. This constant flood distorts our understanding of reality by creating idealizations.

Because images carry intent, they often push desired reactions—whether it’s envy, aspiration, or conformity. Over time, these triggers unconsciously mold self-perceptions.

For instance, curated social media promotes fantasies of perfection, leading viewers into dissatisfaction with their actual lives. This demonstrates imagery’s dominance over emotion.

Gender stereotypes, like submissive portrayals of women, amplify societal expectations. Repeated exposure normalizes these ideals, restricting individual expression and diversity.

Images sell stories beyond the visible. Discerning viewers must actively decode these narratives, questioning: Who benefits from such idealizations? And at whose cost?

As Berger argues, people must engage critically to disconnect personal worth from curated imagery. This prevents media manipulation and fosters self-awareness.

In doing so, we regain autonomy over how visual input impacts our actions, interpretations, and sense of who we are in an image-driven era (Chapter 3).

-

Question Publicity’s Hidden Influence

In today’s world, publicity images dominate perception. They don’t just sell; they shape desires. Recognize this context before engaging with such imagery.

Know that publicity presents filtered realities, designed to elicit envy and promote consumption. They portray idealized versions of life, urging continuous consumerist pursuit.

To counter this, practice critical viewing. Ask whose story is elevated, why it’s presented this way, and what societal values it enforces.

This reflective approach clarifies how consumer society values ownership over authenticity, shaping identity in ways that aren't true to ourselves.

Developing skepticism toward publicity creates empowerment. It lessens external validation's hold and reduces unnecessary materialistic comparisons.

Moreover, critical awareness enriches decision-making: You’ll focus on genuine needs over superficial motivations shaped by ads or curated media.

By viewing incoming messages critically, you’ll protect self-worth against fleeting illusions. A questioning approach leads to stronger, authentic connections with yourself and others.

-

Embrace Context in Image Interpretation

When engaging with art or media, understand that context always colors the story. To grasp full meaning, dive beyond what appears at first glance.

Consider the background—historical, cultural, or economic—behind an image’s creation and presentation. Recognizing these factors reveals deeper nuances and interpretations.

Instead of passively consuming visuals, actively ask: Who created this? What purpose does it serve? By doing this, you regain control over its narrative's intent.

This practice encourages a more informed relationship with media messages. It counteracts shallow, prescriptive consumption often linked with quick advertising formats.

Understanding context enriches both critical thinking and emotional reactions. It humanizes the subjects displayed in images, enhancing connections beyond superficial levels.

Long-term, this practice fosters mindfulness, helping differentiate between representation and reality, reducing manipulation by external influences.

In a world dictated by visuals, curiosity ensures images aren’t just consumed—they’re understood and evaluated meaningfully, respecting their layered complexity.

-

Society’s Power Defines Art

Art is deeply tied to societal power structures. Its production and visibility reflect broader political and cultural dynamics present during its creation.

Historically, ownership by elites defined artistic narratives. Artworks often aligned with their ideals, amplifying perspectives of power holders, marginalizing alternative voices.

This power imbalance influences today’s visual culture. People rarely question curated museum exhibitions or ads, which silently reinforce ruling-class perspectives.

Berger invites viewers to decode these dynamics—asking questions about who owns, distributes, or benefits from what’s seen. This uncovers hidden social hierarchies.

Art's commodification further complicates this. It pushes monetary worth, diluting deeper emotional, activist, or sentimental connections embedded in creation.

By recognizing this distortion, individuals can resist shallow perspectives. Seeing art critically reveals its broader cultural role in maintaining or challenging systems of control.

This vigilance helps demythologize visuals, allowing art to break free from systems that define it narrowly, promoting richer, multifaceted perspectives (Chapters 5–7).