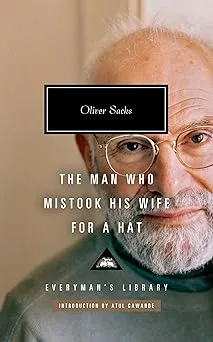

About this book

Five Key Takeaways

- Brain damage can distort perception of reality and identity.

- Proprioception is crucial for maintaining a sense of self.

- Our identity is closely tied to bodily awareness.

- Emotional tone persists despite language loss in aphasia.

- Memory and nostalgia significantly shape our present identity.

-

Brain Injury Alters Object Perception

Dr. P., a patient with visual agnosia, struggles to recognize objects correctly, mistaking his wife's face for a hat (Chapter 1).

This condition stems from brain damage, which disrupts the brain's ability to integrate visual information into meaningful understanding. It separates recognition from context.

Dr. P. sees details like shapes and colors but can't relate them to their functions, making his perception fragmented and mechanical.

His story illustrates how neurological disorders strip away emotional connections, resulting in a sterile experience of reality where symbols replace human meaning.

In daily life, this manifests as awkward social interactions and disconnection from loved ones, underscoring how perception shapes our relationships.

Such cases challenge our understanding of identity. When the mind misinterprets what the eyes see, the human connection often diminishes.

This fact highlights the brain's reliance on both sensory input and context for full interpretation. Perception, it turns out, is far from simple.

The larger implication? Disorders like agnosia show how fragile yet complex the unity of perception, emotion, and cognition truly is.

-

Proprioception Is Crucial to Identity

Christina’s experience reveals a major problem: losing proprioception—a sense of body awareness—can profoundly disrupt one’s physical sense of self.

Post-surgery, Christina struggles to "feel" her body, relying solely on vision to move. Her disembodiment leads to frustration and alienation.

This problem is huge because proprioception is vital for instinctive, unconscious movements. Without it, every action becomes painstakingly deliberate.

Dr. Sacks argues that such cases illuminate how identity is rooted in the intricate feedback loop between body and mind.

Christina’s resilience, achieved through visual training, supports the belief that the human brain has an incredible capacity to adapt even under distressing conditions.

This perspective shows the shocking vulnerability of the human mind-body relationship and how one small change can ripple across daily life.

The lesson is humbling: while human adaptability is remarkable, a loss of coordination between body and mind challenges core self-concepts.

By focusing on recovery and sensory balances, Dr. Sacks demonstrates that the relationship between bodily awareness and identity must never be underestimated.

-

Phantom Limbs Persist After Amputation

Amputees commonly experience phantom limb sensations, feeling pain or movement in limbs that are no longer physically present (Phantom Limbs section).

These sensations occur because the brain retains neural maps for the lost limb, blending memory and perception into a confusing reality.

The phenomenon emphasizes that our body image is not limited to physical presence—it’s deeply tied to cognitive and neurological networks.

Phantom limbs complicate rehabilitation, as the patient struggles to reconcile their mind's image of the limb with its actual absence.

This profound brain-body discrepancy reveals the incredible persistence and adaptability of neural memory, even as physical conditions change.

Phantom limbs challenge our binary understanding of loss and identity, showing that memory deeply participates in our sense of self.

This fact has therapeutic implications, such as using mirror therapy to "trick" the brain into acknowledging the limb’s absence.

Ultimately, it reveals a fascinating truth: our sense of self is tightly knit with our brain’s inner maps, even more than our physicality.

-

Focus on Emotional Tone When Speaking

Patients with aphasia, who can’t process language, still understand emotional tones in speech. This offers an opportunity for emotional connection.

To communicate effectively, prioritize your tone over words. Keep it consistent with the feelings you want to convey.

For loved ones and caregivers, vocal emphasis, rhythm, and warmth can ensure connection, even when language barriers exist.

This is crucial because emotional understanding persists longer in neurological disorders, forming a vital bridge of human interaction.

Patients respond vividly to genuine feelings, fostering reassurance and connection. Without this approach, communication can feel hollow or alienating.

Providing emotional engagement creates trust and rapport, counteracting the isolation neurological impairments often bring to patients.

By embracing emotional tones as a communication tool, you'll be giving them a profound way to engage with the world.

-

Identity Depends on Physical Awareness

A man awakes rejecting his own leg as alien, showing how deeply identity is tied to body ownership (The Man Who Fell Out of Bed).

He’s horrified to find his "strange" leg next to him, shattering his psychological sense of personal unity.

This problem amplifies the existential crisis many experience: how do we understand ourselves when physicality feels foreign or disconnected?

Dr. Sacks suggests that losing alignment between body and mind attacks the heart of how we humans perceive selfhood.

Such cases force us to rethink identity as something co-created by brain, body, and experience, rather than purely mental constructs.

Neurological disruptions provide a haunting example of how fragile our unity really is and demand deeper awareness of mind-body integration.

This insight pushes us to explore a vital question: how much do we define who we are based on our physical continuity?

Through psychological and medical care, rebuilding bodily awareness can rebuild not just coordination but a person's sense of personhood itself.

-

Music Evades Cognitive Decline

Dr. P., despite cognitive impairments and agnosia, retains his musical abilities, using them as a mental refuge (Chapter 2).

This disconnect between his visual deficits and musical competence shows how certain brain functions remain intact despite severe disorders.

Music appears to activate regions of the brain less affected by agnosia, making it a potential therapeutic tool for neurological patients.

This fact highlights the school of thought that music is neurologically fundamental—it bypasses language and taps into emotional cognition.

For patients like Dr. P., music isn’t just a skill; it’s a mode of existence that allows identity and joy to persist.

These cases emphasize how art and creativity provide emotional sustenance, even when other cognitive systems deteriorate.

The therapeutic implication is significant: nurturing creative expression could improve mental well-being for patients with neurological challenges.

By fostering creative outlets, we access deep human resilience, proving again that the mind adapts even when parts seem irreparably broken.

-

Use Vision to Compensate Proprioception Loss

Patients with proprioceptive disorders, like Mr. MacGregor, struggle with awareness of bodily movement but adapt by relying on vision.

To regain functionality, train yourself to use visual cues to gauge your spatial orientation and movements deliberately.

For example, look at your feet when walking or track hand motions when grabbing objects to replace lost sensory feedback.

This adaptation is powerful because vision acts as a compensatory system, bridging gaps created by proprioceptive failure.

Without training, everyday activities such as walking or cooking could remain fraught with difficulty and frustration, eroding independence.

Using this strategy fosters self-reliance while minimising injury risks in compromised patients, providing greater confidence in movement.

By embracing visual strategies, rehabilitation can unlock renewed mobility and functionality, offering hope amidst proprioceptive deficits.

-

Human Resilience Shines in Disability

From Christina to Ray, the book demonstrates that neurological challenges often reveal human adaptability and hidden strengths.

Despite profound losses, patients navigate their altered realities with creativity, humor, and new coping mechanisms, redefining resilience itself.

This resilient spirit highlights how the mind and brain seek balance, finding pathways to preserve normalcy even when systems collapse.

Dr. Sacks argues that these examples inspire hope, proving that even extreme adversity can reveal untapped potential in individuals.

This perspective challenges the notion of weakness in disability, reframing it as fertile ground for alternative strengths and identities.

Underlying this opinion is an optimistic belief in rehabilitation, personal growth, and the human capacity to adapt emotionally and mentally.

The lesson is profound: neurological challenges force society to rethink how it measures strength, ability, and humanity.

By celebrating human resilience, Sacks advocates for compassion and support that uplifts patients and unlocks their potential to thrive.